Interview with "The Cartel" Author Don Winslow [FEATURE]

The best-selling author of The Savages sits down with the Drug Truth Network to discuss his new novel, The Cartel, and the futility of drug prohibition.

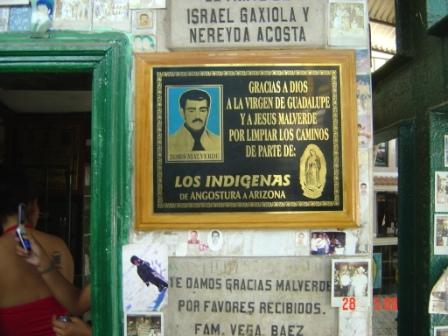

shrine to San Malverde, patron saint of the narcos (and others), Culiacan, Sinaloa -- plaque thanking God, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and San Malverde for keeping the roads cleans -- from "the indigenous people from Angostura to Arizona" (more pictures below the fold)

I visited the shine in the heat of the afternoon sun today. During the half hour or so I was there, a few dozen people came to light candles to the santo, pay their respects, or otherwise recognize his alleged powers of protection. A handful of musicians for hire hung around, waiting for someone to pay them to play a tune to the saint, and about a dozen vendors sold San Malverde memorabilia--candles, plaques, good luck amulets, prayer cards, and the like. (Hmmm, do I feel an idea for a StoptheDrugWar.org premium gestating?)

The vendors told me that dozens, sometimes hundreds, of people arrive each day, some to pray, some to light candles, some to make donations, some to put up plaques:

shrine to San Malverde, patron saint of the narcos (and others), Culiacan, Sinaloa -- plaque thanking God, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and San Malverde for keeping the roads cleans -- from "the indigenous people from Angostura to Arizona" (more pictures below the fold)

I visited the shine in the heat of the afternoon sun today. During the half hour or so I was there, a few dozen people came to light candles to the santo, pay their respects, or otherwise recognize his alleged powers of protection. A handful of musicians for hire hung around, waiting for someone to pay them to play a tune to the saint, and about a dozen vendors sold San Malverde memorabilia--candles, plaques, good luck amulets, prayer cards, and the like. (Hmmm, do I feel an idea for a StoptheDrugWar.org premium gestating?)

The vendors told me that dozens, sometimes hundreds, of people arrive each day, some to pray, some to light candles, some to make donations, some to put up plaques:

"Thanks to God and San Malverde for favors received." "Thanks to God, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and San Malverde for helping us move forward." "O miraculous Malverde, O, Malverde my Lord, Concede me this favor, And fill my heart with happiness."Given the way Mexico's drug war is raging these days, I would imagine the good saint is getting a real work-out. Mexicans are so inured to the daily drug war death toll that the newspapers generally relegate it to box score-type accounts, but when you or a friend or a family member is working in the trade, you probably figure some supernatural help can't hurt. I'll spend the next few days here in Culiacan. I had wanted to go up to the drug-producing areas in the mountains nearby, but so far, everyone is demurring--it's too dangerous, they say. Nonetheless, I'll keep working that and see what happens. On Tuesday and Wednesday, I'll be attending and "International Forum on Illicit Drugs: The Merida Initiative and the Experiences of Decriminalization," organized by the brave journalists of the Culiacan news weekly Riodoce. While the other Sinaloa papers have largely gone silent in the face of threats and killings, Riodoce keeps plugging away. I'll be meeting with some of the Riodoce staff tomorrow, right after I meet with Mercedes Murillo, head of the local human rights organization the Sinaloa Civic Front, which just a couple of days ago filed what could be a historic court motion to have military personnel accused of crimes against civilians tried in civilian--not military--court. There have been several nasty incidents of soldiers killing civilians here since Calderon sent in the troops, and under current Mexican law, they seem to get away with it. Stay tuned. It should be an interesting week. And then it's back to Mexico City to visit Saint Death and attend the Global Marijuana Day demonstration at the Alameda. (more pictures below the fold)

The cartelâs supply chain is embedded in the huge legal bilateral trade between the United States and Mexico. Remember that Mexico exports $198 billion to the United States and â according to the Mexican Economy Ministry â $1.6 billion to Japan and $1.7 billion to China, its next biggest markets. Mexico is just behind Canada as a U.S. trading partner and is a huge market running both ways. Disrupting the drug trade cannot be done without disrupting this other trade. With that much trade going on, you are not going to find the drugs. It isnât going to happen. Police action, or action within each countryâs legal procedures and protections, will not succeed. The cartelsâ ability to evade, corrupt and absorb the losses is simply too great. Another solution is to allow easy access to the drug market for other producers, flooding the market, reducing the cost and eliminating the economic incentive and technical advantage of the cartel. That would mean legalizing drugs. That is simply not going to happen in the United States. It is a political impossibility. This leaves the option of treating the issue as a military rather than police action. That would mean attacking the cartels as if they were a military force rather than a criminal group. It would mean that procedural rules would not be in place, and that the cartels would be treated as an enemy army. Leaving aside the complexities of U.S.-Mexican relations, cartels flourish by being hard to distinguish from the general population. This strategy not only would turn the cartels into a guerrilla force, it would treat northern Mexico as hostile occupied territory. Donât even think of that possibility, absent a draft under which college-age Americans from upper-middle-class families would be sent to patrol Mexico â and be killed and wounded. The United States does not need a Gaza Strip on its southern border, so this wonât happen. The current efforts by the Mexican government might impede the various gangs, but they wonât break the cartel system. The supply chain along the border is simply too diffuse and too plastic. It shifts too easily under pressure. The border canât be sealed, and the level of economic activity shields smuggling too well. Farmers in Mexico canât be persuaded to stop growing illegal drugs for the same reason that Bolivians and Afghans canât. Market demand is too high and alternatives too bleak. The Mexican supply chain is too robust â and too profitable â to break easily. The likely course is a multigenerational pattern of instability along the border. More important, there will be a substantial transfer of wealth from the United States to Mexico in return for an intrinsically low-cost consumable product â drugs. This will be one of the sources of capital that will build the Mexican economy, which today is 14th largest in the world. The accumulation of drug money is and will continue finding its way into the Mexican economy, creating a pool of investment capital. The children and grandchildren of the Zetas will be running banks, running for president, building art museums and telling amusing anecdotes about how grandpa made his money running blow into Nuevo Laredo. It will also destabilize the U.S. Southwest while grandpa makes his pile. As is frequently the case, it is a problem for which there are no good solutions, or for which the solution is one without real support.This is the situation the Bush administration wants to throw $1.4 billion at in the next couple of years. Maybe it and Congress should be reading Strategic Forecasting analyses, too.